Recognising the relative decline of viticulture, during the 1990s the Aude departmental council began a push to develop tourism as an alternative player in the local economy. This coincided with the EEC[1]’s Set-aside policy which was an incentive scheme to help reduce the large and costly surpluses produced in Europe under the guaranteed price system of the CAP[2]. Set aside was designed to deliver environmental benefits in the wake of extensive damage to agricultural ecosystems and wildlife (sic) resulting from the intensification of agriculture. It sought to achieve this by requiring that farmers leave a proportion of their land out of intensive production. Such land was said to have been ‘set aside’.

As viticulture is the principal agricultural activity in the Corbières, the set-aside scheme was most often used to return vineyards to nature. According to reports from television channel France 3[3], wine production in the Occitanie region (in which the Corbières are situated) fell by a third between 1993 and 2023. This is an indication of the amount of land taken out of wine production and returned to nature and some used for other purposes such as house-building or commercial activities.

Inevitably social and political challenges have an impact on land use which in turn impacts the lives of non-humans that live on the land. This type of anthropogenic environmental impact ranges from set-aside making new lands available to non-humans; to land that non-humans have been using now being taken from them for human use such as roadbuilding, or development of tourist sites. My research will aim to illuminate key examples of these types of anthropogenic environmental impact with reference to ‘sharing out’ of land between human and non-human animals.

The climate emergency is a second, arguably more impactful, environmental consequence of human activity and its presence has been keenly felt in the Corbières for some years. The two most noticeable manifestations of the climate emergency in the region are hotter summers with long periods of much higher-than-average temperatures; and lack of rain leading to severe drought. As a result, the forests are exhausted and trees are dying (Vitasse, Wohlgemuth and Rigling, 2023). Non-humans are affected in numerous ways, frequently leading to human-non-human animal conflict.

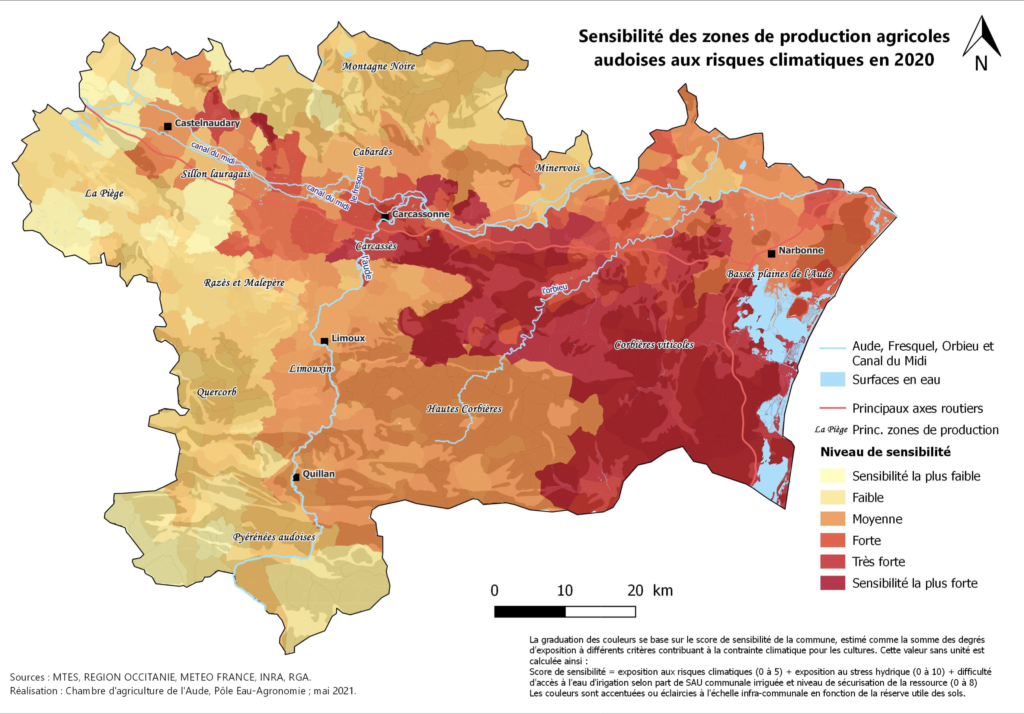

In its current resumé showing that ‘the effects of climate change are multiplying’, the Aude Chamber of Agriculture[4] (CAA, 2024) states[5] : ‘All farms in the department are exposed to climatic risks. Some areas, such as the Corbières, have a great number of risks’. Less than 10% of the departmental agricultural area is irrigated, 41% of the Utilised Agricultural Area (UAA[6]) is completely devoid of possibilities of access to secure water resources, and almost all the cantons of the department have soils with an organic material content of low to very low.

The map at Figure 7 (below) illustrates these risk factors as they were in 2020 with the areas in red being those where climate change is being most felt. The Corbieres is completely contained within this red area. Moreover, it should be borne in mind that since 2020 summer temperatures have increased further and, despite occasional rain, drought has been endemic.

A different public service information website, Info Secheresse (2024), states that the water tables across the Aude, including the Corbières, and in the next department to the south, the Pyrenées Orientales, are at the lowest levels of all departments in France. The drought situation is so severe that in the village where I am focusing my research, the government drought information website (Vigieau, 2024) instructs residents that: Drinking water is on heightened alert at your address’. It goes on to say that there is a:

“Reduction of all water withdrawals and ban on activities impacting aquatic environments. Reinforced restrictions on watering, filling and emptying swimming pools, washing vehicles and irrigating crops”.

Figure 8a (below) shows the usual level of water in the ‘lavoir’ (washing) area of the Ruisseau[7] just below my garden and orchard. Figure 8b shows the water level on 24th May 2024.

In Figure 8a the entire lavoir is full and the water is running quickly as the stream is constantly replenished by water from springs higher up in the hills, which in turn are replenished by rainwater. In figure 8b, only the dammed area of the lavoir contains water and that water is barely moving as there has been little rain, so springs have dried up.

I have already obliquely referenced Government concerns for the climate emergency unfolding in southern France including the Corbières region, by citing examples of official information websites aimed at farmers and the public. Lack of time and space prevent me from elaborating on the multifarious ramifications of the climate crisis on human and non-human animals in the Corbières, but these will be an important aspect of my research.

The situation on the ground is changing so rapidly[8], that peer reviewed material is not keeping pace with political discussions and decision-making as manifestations of anthropogenic climate change grow ever-more apparent, and an increasing number of people grasp the reality of what is happening.

Local, departmental and regional politicians need up to the minute intelligence to be able to respond to changing conditions, and the local press see an important part of their role as being to both provide information to the community and to feed community views to politicians. Government information is also distributed to local politicians as well as to local news services. Local businesses, growers and residents rely on newspaper reports based on this information.

This is in line with findings of Jenkins and Nielsen (2018) who found that in the digital era, local newspapers that are successful aim for local depth and breadth and seek to sustain themselves through premium content and subscription models[9]. These newspapers are often highly tailored to the specific areas they serve (…) Over time, their emphasis on a more targeted geographic area and audience also make them more dependent on local support. Unquestionably, one must proceed with care here, for newspaper reports are not always intended to be unbiased[10]. Nonetheless, I use them in this paper as a source of current information to help build a picture of the impact of climate change in the Corbières, as well as an illustration of the kinds of information that is directly informing the knowledge base and attitudes of much of the human population.

As a result, to be as up to date as I can be, I will draw from the latest reporting by scientific advisers, science correspondents and local reports providing information to the politicians, professional organisations, and general population of the Aude (including the Corbières).

For example, in January 2023, agroclimatologist, and climate photographer Dr Serge Zaka, (La Dépêche, 2024), discussed some of the ways in which climate change is impacting on the Aude department. For Zaka, the situation is now so acute, that he suggests that very soon people in the Aude will have to choose between tourism or agriculture. He is clear that the environment will not be able to support both, for each of these activities requires considerable quantities of water in a region where:

…at less than 200 mm of cumulative rainfall, we are in fact at the classification threshold for arid climates; between 200 and 400 mm, we are in semi-arid conditions. This shift, with a transition from a Mediterranean climate to an arid climate, has taken place practically without transition, in two years. Of course, to qualify as climate change, it must be observed over a longer period. (La Dépêche, Antoine Carrié in conversation with Serge Zaka, 2024)

Zaka’s reading of the latest scientific evidence at the beginning of this year was that in the last three years the climate of the Corbières has switched from Mediterranean to Arid. In his interpretation of the available data, Zaka felt confident to predict that between 2024 and 2050 this new climate will establish itself as the norm and that this change will have an important impact on the economic life of the region.

Only four months later, Véronique Durand in L’Independant of 26th May 2024, reported on the distress being caused to older winegrowers in the Corbières. In areas without direct access to water supplies for irrigation, growers are being compensated – not enough in their view – for destroying their vineyards and returning the land to nature.

Leave a reply